“Having compassion doesn’t mean we can’t take a stand. It’s important to speak up when we’ve been hurt, when we see others being hurt, and when we observe or experience examples of abuse of power. It is equally important to listen deeply and without judgment when people speak about their experiences and their suffering. What has been dysfunctional does need to be openly addressed. We are at a time when old systems and ideas are being questioned and falling apart, and there is a great opportunity for something fresh to emerge. I have no idea what that will look like and no preconceptions about how things should turn out, but I do have a strong sense that the time we live in is a fertile ground for training in being open-minded and open-hearted. If we can learn to hold this falling apart–ness without polarizing and without becoming fundamentalist, then whatever we do today will have a positive effect on the future.”

– Pema Chodron

Several years ago I had the opportunity to visit the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee. I grew up in the ’60s in Chicago. It was a turbulent time in our country’s history. There were assassinations of people who many of us considered heroes: Martin Luther King, Jr., John F. Kennedy, and Robert Kennedy. Violent riots in Detroit, Chicago, Baltimore, Washington D.C. and many other cities. The Cuban missile crisis put us on the brink of global nuclear war. There were dozens of campus protests against the Vietnam War, one of which led to the killing of students by National Guard troops in Ohio. And the federal government sent National Guard troops to Alabama to challenge a state’s refusal to allow school integration. And more.

There was tremendous polarization at the time. Not necessarily based on political party, and not only on race. But there was also a deep generational polarization. And polarization based on support and opposition to the Vietnam War.

Many people thought that our country would never recover from this decade. But we did. Things changed. Some issues were resolved. Others persisted.

One of the reasons things changed the way they did is because people (lots of people) took action. Some of those people were killed for speaking up and taking action. Others suffered retribution and paid a price in other ways.

I have been a student of action for many years, particularly the past 32 years as I studied and taught Japanese Psychology, an approach that generally puts more emphasis on action and less on talk than traditional western psychotherapy. But even before my introduction to Japanese Psychology, I remember attended a national Buddhist conference in Colorado in the 1980’s with Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese Zen teacher. The organizers, to their credit, had also invited an activist, Abbie Hoffman, who chastised the audience for “naval-gazing” while people suffered in the world. He said that the theme of peace was pretty much irrelevant. Just about everybody supported “peace.” The real issue, according to Hoffman, was “justice.” That was a value worthy of our attention and energy – worth fighting for.

It was a thought-provoking time for me – trying to understand how to reconcile a spiritually-based life while taking action to reduce the suffering of others. And doing so in a way that was grounded in compassion. There was a phrase that was born during that time –

“Take your practice off your cushion.”

It suggested that we bring our spiritual values and practice into our daily life and into the world.

Unfortunately, there was no diagram for doing so. No step-by-step directions for assembly. We each had to figure this out on our own. But there were models of compassionate action. In particular, Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. And others, less well-known.

As I review my own understanding of taking action, much of which I recorded in my book, The Art of Taking Action: Lessons from Japanese Psychology, I would like to suggest that there are four primary obstacles to action-taking, whether related to changes in our personal lives, or engaging in activism on behalf of others.

- We don’t know what we need to do

- We allow our feelings to direct our behavior

- We mistake the urgent for the important and fail to act on what’s truly important

- We are unwilling to take the risks that are involved in taking action

It’s not possible to have a thorough discussion of each of these obstacles in a brief essay. So, instead, I’ll offer one comment for each of the issues listed above and, hopefully, that will get you thinking (and acting).

- We Don’t Know What We Need to Do

Many of us assume that figuring out what we need to do is a “thinking” task. But, more often than not, it’s a question of acting. Taking action is often a way of figuring out what needs to be done. We take small steps and three things happen: We see things from a different perspective, things change as a result of our actions, and, we build momentum. So the next time you feel confused and stuck, don’t try to think your way out of it. Take action.

- We Allow Our Feeling to Direct Our Behavior

The principle in Japanese Psychology that attracts people more than anything else is that we can shift from a feeling-centered approach to life (in which feelings rule our lives) to a purpose-centered approach (in which purpose is the director of our life’s play). Feelings remain an important part of our experience, but they don’t determine what we do and when we do it.

- We Mistake the Urgent for the Important (and fail to act on what’s truly important)

The further back from your life you step, the easier it is to see the big picture. What is it that’s important for you to do before the end of the year? What is it that’s important for you to do before you die? Pay attention to what comes up in response to these questions. Now review what you did in the past 24 hours. Is there a match? There are tasks and activities that are both urgent and important. But there are many ways we use our time to address things that appear urgent, but, upon reflection, are really not important . . . when we see the big picture.

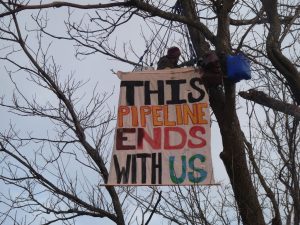

- We Are Unwilling to Take the Risks Involved in Taking Action

For the past 10 years I’ve taught an online course called, Living on Purpose. Periodically I survey the participants and one of the questions I ask is, “Am I taking the risks that are necessary to transform my life in the direction it needs to go?”

Based on nearly 200 responses, about 40% of the respondents indicate that they are taking little or no risk at all. Another 45% say they are taking some risk, but not really enough to move forward according to their goals or dreams. Only about 15% indicate that they are taking significant risks in order to move towards what they believe are important changes in their lives. Many people are willing to take risks if their family’s welfare is at stake. But what risks are we willing to take for our community, for our country, or for the planet?

Joan Baez once said,

“Action is the antidote to despair.”

The reason, I believe, is that despair often comes from feeling the situation is hopeless. And because there is no hope, we may end up doing nothing. Doing nothing is the key ingredient in despair.

But when we take action, constructive action, we feel empowered. We may not prevail. We may not reach our goal. We may not influence the ultimate outcome. But we’ve done what we could do. We feel empowered by our action, regardless of the outcome. And when we’ve done what we can do, we may actually discover faith.

Faith is what awaits us when there’s nothing more we can do. Despair is what awaits us when we do nothing.

Not long ago, I conducted a workshop at a Buddhist center. In many religious traditions, I think spirituality is often equated with passivity – we shouldn’t have goals, we shouldn’t strive for change. But I pointed that many of the founders of Buddhist sects were men of action, including Dogen and Shinran. And many spiritual leaders from a variety of religious traditions were people of action, including Gandhi, the Dalai Lama, and Mother Teresa. In a film recently released, we see Harriet Tubman escaping slavery

and then returning, time and time again, to rescue and lead slaves to freedom. She was a woman of purpose and she overcame each of the above obstacles. She knew what was truly important and what she needed to do. She didn’t let feelings of fear keep her from taking action. And she was willing to assume great risks – risks of torture and death – to accomplish her purpose. At the same time, her efforts were influenced by her spiritual path. She felt God was guiding her as she tried to find a path back to freedom for her and the people she saved.

In closing, I wish to return to the Pema Chodron quote that I offered at the beginning of this essay.

“I do have a strong sense that the time we live in is a fertile ground for training in being open-minded and open-hearted. If we can learn to hold this falling apart–ness without polarizing and without becoming fundamentalist . . .”

We are left with the question of how to take action at this moment of time, and yet do so with an open heart and an open mind. Ultimately, polarization is a denial of the interdependence and oneness of all life, of all sentient beings.

For, in the end,

“Each man’s death diminishes me,

For I am involved in mankind.

Therefore, send not to know

For whom the bell tolls,

It tolls for thee.”– John Donne

Gregg has been teaching and studying Japanese Psychology for the past 32 years. He has written five books, including an Amazon best seller, The Art of Taking Action: Lessons from Japanese Psychology (2014). On February 24, 2020, he will be teaching the online course, Taking Action: Finishing the Unfinished and Starting the Unstarted.

Rhino photo credit — jacqueline macou