Meaningful Life Therapy from Japan provides lessons for how we can live meaningfully even when we are ill.

by Gregg Krech

This past summer I stood in a quiet room and read a eulogy over the body of a man covered with a sheet. His name was Arthur. According to the information I had, he had died quietly in his sleep at the age of 100. I talked about his life — about what he did, what he had accomplished while alive, and how his life impacted on his family and society. When I finished reading the eulogy I asked Arthur some questions.

Arthur answered each question. You see, he’s not truly dead. He’s participating in a training program. He says he wished he had learned to play a musical instrument. He regretted his bad temper — remembering the many occasions he yelled at his wife and children. He talked with satisfaction of the children’s school he helped to start in his community. He cried as he described the lack of contact with his father prior to his father’s death. In this exercise (first described in Playing Ball on Running Water, 1991 by David Reynolds), he, like other participants, was asked to write their eulogy, obituary and epitaph. For some of these individuals this exercise is the closest they have ever come to reflecting on and experiencing death. But this exercise is not really about death. As Dr. Jinro Itami states, “you will learn the value of your life by thinking deeply about your death.”

MEANINGFUL LIFE THERAPY IN JAPAN

Dr. Itami is the founder of Meaningful Life Therapy (MLT) in Japan. MLT is a psycho-educational program that provides guidance, support and skills for those who are suffering from serious illness, primarily cancer. It complements the patient’s medical treatment and is based on the premise that the mind and body are not separate. The patient’s attitude and life activity impact on their health. Several characteristics of MLT are noteworthy when compared to efforts in the U.S.:

An Active Life

The motto of the MLT program members is,

“Even though I am ill, I will not live like a sick person.”

In fact, the lives of these cancer patients are more full and active then many healthy people. When Emiko Kuramoto was operated on for breast cancer she was told she had a 60% chance of living more than five years. She became very depressed and wanted to quit her job and just live out the rest of her life peacefully. But Dr. Itami encouraged her to be active and do everything that she could do. He suggested that what she did with her life was more important than trying to create a feeling state of “peacefulness.”

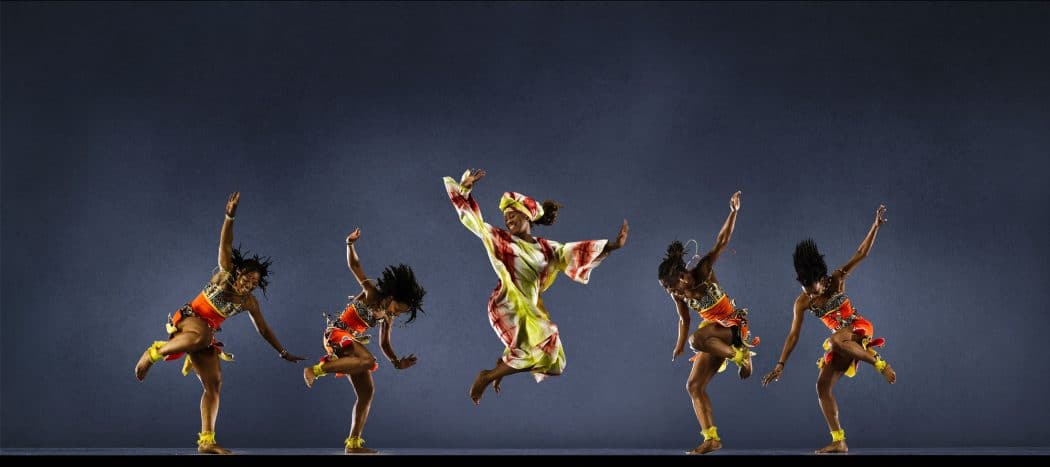

He invited Ms. Kuramoto to join him and other cancer patients on mountain climbing expeditions. In the year after her operation, she climbed three mountains in the Japanese Alps.

“This experience helped me recover my spiritual strength a little,” she states.

She later joined Dr. Itami and six other cancer patients on an assault of Mt. Blanc, the highest peak in the European Alps. While she did not quite make it to the summit, her friend, Kazumi Bansho, was one of the three patients who did succeed in making it all the way.

“We succeeded in the Mont Blanc ascent because of the fighting spirit we learned from MLT. We faced the fear of death five times — while climbing; while we were crossing the landslide area; when we met the severe snowstorm; when we heard thunder; and when we were going down the snow and ice covered rocks. These were opportunities to practice what we learned. We must devote ourselves to what we can do now, while coping with the fear of death.”

Though not all MLT members participate in mountain climbing, it is symbolic of the program’s emphasis on an active life of accomplish challenging and meaningful goals. For some patients it is artwork, for others it is finishing college. Each of these cancer patients is demonstrating, in their own way, that they will not allow themselves to be defeated by their disease. Their courage and determination demonstrate to family, friends and all of society that people with a serious illness can accomplish much more than we generally expect them to do.

Dr. Itami believes that this kind of meaningful activity and fighting spirit has a direct effect on the body’s immune system and therefore on the progression of the disease. His expectations are born out by a growing amount of research, such as a study published in The Lancet which indicated that those patients with “fighting spirit” had the longest survival rates.

In the MLT program mutual support is more commonly found “activities” like mountain climbing or gardening, rather than therapy groups in which people primarily sit and talk. The active lifestyle that MLT advises promotes strength of both character and body. The use of the body promotes a more psychologically healthy state of mind — which in turn influences the body. Robert Ader, Ph.D., the Director of Behavior of Psychosocial Medicine at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, states,

“I find it a little bit unbalanced that we talk more about how the mind can be taught to influence the body than about how the body can influence the mind.”

Helping Others – What can I do for you?

In the eulogy exercise I mentioned earlier, participants must deeply reflect upon their own life and death. In doing so, many participants realize the value of doing something which is useful to others. They often imagine accomplishments which will benefit others even after they die. If we feel we are useful and that our life provides some benefit for others, our will to live (sei no yokubo in Japanese) is increased. But patients with serious illness are too often encouraged to “relax” and “take it easy.” Through our efforts to care for them we relieve them of their role as “helpers” and make them helpless. To strengthen their body and spirit we must encourage them to maintain activities which benefit others and give their life meaning.

In Japan, cancer patients are frequently invited to lecture at nursing schools and groups of patients gather to clean a park or pick up trash along the road. Even those who are bedridden can often write letters or make crafts. When I visited the cancer wards at Shibata Hospital in Kurashiki, I was inundated with gifts of crafts and poems from the patients I met. I was very touched by their spirit of giving themselves away even in the midst of their own suffering.

Other admirable components of this Japanese program include:

Humor therapy

Patients meet regularly and must give a 2 minute humor speech which makes the rest of the group laugh. The participants are encouraged to poke fun at themselves. As a result, they constantly are looking for the humor in their experience so they can be ready when it is their turn to be a “stand-up” comic. Dr. Itami believes that laughter has beneficial effects upon the body’s immune system.

Responsibility for one’s Health

Participants in the program are encouraged to take responsibility for their own health care decisions, rather than passively follow doctor’s orders. They are encourage to read, study and learn about their disease so they can make wise, knowledgeable decisions.

Coping with Anxiety and Fear

The MLT program is founded upon the principles of Morita Therapy, a method of psychotherapy developed in the 1920’s by psychiatrist, Shoma Morita, M.D. Morita therapy suggests that feelings, such as fear and anxiety, are not controllable directly by our will. We cannot simply tell ourselves to feel confident, serene or happy. Through our willpower, we cannot get rid of anxiety, depression or fear of dying. So Morita Therapy advises people to use a martial arts type of approach to dealing with unpleasant feeling states — notice them and accept them, but do not offer resistance. Forms of resistance, such as denial, or even trying to “change” your feelings, simply give them more power. It is better to simply acknowledge one’s feelings, learn to co-exist with them and allow them to pass naturally.

Morita Therapy is rooted in the psychological principles of Zen and those familiar with Zen will often see the similarities between Zen meditation and Morita’s guidelines for dealing with unpleasant feeling states. MLT members receive guidelines in applying these principles to their own states of anxiety and fear of death. They readily learn to co-exist with such feeling states rather than trying to attain some artificial state of psychological comfort in the midst of their struggle for life and health.

Conclusion

Each and every one of us is alive today. A mysterious spark of Life keeps our hearts pumping, our lungs breathing. As long as we are alive, shouldn’t we be students of Life, studying the question, “How shall we live?”

Many years ago I had a student by the name of Nick who had AIDS. He was an excellent student and worked very hard to apply these principles to his life while he was ill. He once participated in a training program at the ToDo Institute called “A Day of Mindful Living.” During this program we all attempt to bring a quality of mindfulness and attention to everything we do. Nick was painting a wicker basket using a can of spray paint, when a gust of wind blew the basket off the table. As a result it needed additional paint from the can of spray paint. He pushed the button to apply more paint, but nothing came out — he was out of paint.

Nick died the following summer from AIDS. He himself had run out of paint. But I still have the wicker basket he repaired. I also have several gifts I received from him. He was an artist and designed the covers of several audio programs. He also designed my stationery. So in a way, he has not really died. He lives on in what he has done and what he has given away. We all do. The legacy of our life is being created this very day. What will it be?

Tags: Living Fully with Illness Meaningful Life Therapy Morita Therapy