By Gregg Krech

“There is rhythm in everything.”

– Miyamoto Musashi

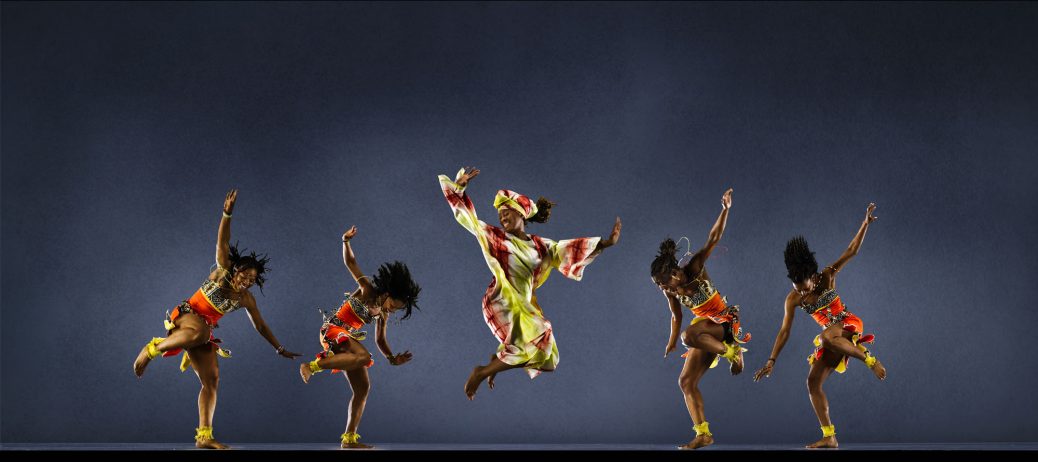

When you listen to a song, you may be aware of its rhythm. Many songs introduce you to the rhythm before the lyrics or melody. So in the beginning of the song, you may simply be aware of the rhythm. I used to have a small personal recording studio, and when recording a song, the first thing you do is establish the rhythm. You might record a metronome beat or a “drum track” and that would be the foundation of the song’s timing. If you dance to music, you’re generally not dancing to the melody or lyrics, you’re dancing to the beat or the rhythm. If the tone of that rhythm is deep, like a bass guitar or a bass drum, your body can actually feel the vibrations. Because your body tunes into the rhythmic vibrations, you don’t even have to think about the music. Your body just moves in sync with the rhythm.

Many people have a basic rhythm to their day, or at least their morning. The rhythm isn’t really about what’s being done (brushing teeth, making coffee), it’s the pace and timing of how it’s done. Think about your morning rhythm. Do you start out very slow and then speed up in the last ten minutes because you realize you are running late? Do you have a relatively even pace from the time you get out of bed until the time you get in your car to leave for work? What about your kids? How would you describe their pace/timing on a weekday morning as they prepare for school?

Even within a particular morning, there is a rhythm to our specific activities. For example, I have a rhythm to making coffee in the morning. There is also a rhythm to the speed with which I walk through the house. There is a rhythm to my riding a bike and to putting the groceries away. You may not be aware of your rhythm as you move from activity to activity, but it’s there.

“The rhythm with which things progress, and the rhythm with which things deteriorate should be understood and differentiated.”

– Miyamoto Musashi

Prior to my sophomore year of college I worked at a UPS distribution center in Northbrook, Illinois. My job was to load packages on to the UPS trucks — not the delivery trucks that come to your house, but the long semi-trailers that you see on the interstate. In the distribution center there were literally miles of assembly line belts that delivered the packages right into the front of these trailers once they were sorted by zip code. I would be assigned to a particular truck and my job was to get the package as they came off the belt and then carry them towards the back of the truck where I would stack them in a tight wall so it could be transported without damage. We had been trained in a particular strategy for loading the trucks and to do it correctly we had to be attentive to the proper way of stacking the packages. The challenge was that the speed in which packages arrived on the belt varied tremendously. Sometimes a box would come and I would pick up the box, walk to the back of the truck, and carefully consider the best spot for it according to my design strategy. Then I would walk back to the end of the belt and watch as another package as it came towards me. But then, suddenly, the packages would start coming closer together, and by the time I had stacked one package, there were 2-3 more already in the truck waiting for me. So you can probably guess what I had to do. I had to speed up. I had to adjust my rhythm to meet the rhythm of the incoming work.

Perhaps you’ve had this experience in your life. You find yourself in a situation where the packages are coming at you very fast. It feels overwhelming. So you speed up to try to meet the demands you’re faced with. That’s fine. The problem is that you develop a fast rhythm and start to apply that to every situation in your life. But not all situations call for a fast rhythm. I recently read a story about a father who was almost always working at a fast pace at his job. In the evening, he had trouble slowing down and relaxing, even when there was no time pressure. He would put his 2 year old son to bed and every night he would read him a bedtime story. But he became very impatient with the pace of the story, so he would speed up his reading, even if it meant his son couldn’t quite follow the story. One day he heard about a book called, “Sixty Second Bedtime Stories” and he thought, “This is great.” Now he could get through the story in just one minute. Fortunately, a light bulb went off for him. “Wait a minute. This is a special time for my son and me. Why am I trying to rush through it?”

The problem is that we can develop a habitual rhythm, and then it becomes difficult for us to adjust our rhythm to the needs of the situation. My initial training in Zen was at a Rinzai Zen temple in Japan. We did walking meditation in between the periods of sitting meditation. We walked in a circle very fast – almost running. That was the style I was taught in that type of Zen training. A few years later I was training with Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Zen teacher. He also taught walking meditation, but he taught us to do it slowly. Verrrrrrry Sloooooowly. This felt extremely awkward at first and I found it hard to concentrate and adapt to this style. It took a while before it felt somewhat comfortable.

The key is to be able to adjust our rhythm to the needs of the situation. If we are packing in the morning to catch a flight we may need a rather quick pace. If we are reading a bedtime story to our daughter, we may need a rather slow, relaxed pace. There is no ideal rhythm for our life, just as there’s no ideal rhythm for music.

There’s one “glitch” to this principle. You may have noticed that it’s generally easier to keep your attention focused on what you’re doing when you are doing it at a “moderate” rhythm. If we go too fast, we tend to lose our focus and our mind races ahead of our body. But if we go too slow, we can find that the mind begins incessant chattering about things that have nothing to do with what we’re doing — so we also lose focus. This doesn’t mean we should try to work at a moderate pace. It simply means that we need to stay focused on the present, regardless of our rhythm. Whether you’re dancing a tango, a fox trot or the Texas two-step, keep your attention on what’s happening in the present moment. Then you can enjoy bedtime stories as well as the chaos of getting your kids off to school.

From our perspective it’s easy to see the rhythm of the seasons or the rhythm of the day and night. From the perspective of the Universe (i.e. God/Buddha), we are a beat in a much larger rhythm. Our life is single beat on the bass drum or a single crash of a cymbal. It’s a timeless rhythm. So make sure you come in on time.

Gregg Krech is a leading expert in Japanese Psychology and his new book, The Art of Taking Action: Lessons from Japanese Psychology will be available on September 20, 2014. He will be teaching the online course, A Natural Approach to Mental Wellness, sponsored by the ToDo Institute, which begins on September 16th.